The first flights

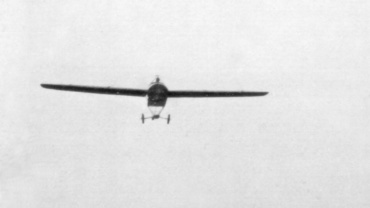

On 4 May 1912, at Bétheny, near Reims, Francesco Baracca took off from the ground for the first time, in the front cockpit of the monoplane piloted by Marcel Hanriot, son of the owner of the civil flying school, Renè. Such was the surprise and emotion felt during that short flight that François couldn’t wait to share it with his father, in a long letter: “I never cease to congratulate myself on having managed to remove myself, at least for a while, from the monotonous life of the regiment and devoting time to a more sporting and varied life. I came to aviation without even knowing so much about it, but now I realise that I had a wonderful idea, because aviation has progressed immensely and it will have an amazing future […] As soon as the engine started, the Hanriot took off through the air like an arrow, and when it left the ground I did not feel a thing, because the aircraft was so stable. […] It was a marvellous daydream to see the trees, the roads, the countryside below me; it’s a very pleasant thing to look down and I didn’t feel dizzy at all.“

At Reims, training proceeded gradually, as the students learnt to taxi in a straight line and then slowly detach themselves from the ground, performing simple manoeuvres. There was plenty of free time, and Baracca and his companions enjoyed the social life of Reims, familiarising with their French colleagues and occasionally travelling to Paris, the undisputed capital of the Belle Époque. After obtaining the French Aeroclub’s pilot’s licence No. 1037 on 9 July, Francesco returned to Italy and reported for duty to the Battaglione Aviatori (Aviators Battalion) at the La Marmora Barracks in Turin.

Here he received instructions to attend the Cascina Malpensa Military Flying School, directed by Captain Moreno. He was assigned, to his great satisfaction, to pilot the Nieuport monoplane. To do so and obtain his license, he had to repeat all the previous tests. Due to the large number of trainees and the scarcity of means, the new training progressed slowly and Baracca consoled himself horseback riding and following the cavalry manoeuvres that were taking place near Malpensa.

In mid-October, he began testing for his military pilot’s licence on a Nieuport, thus obtaining the coveted badge of the eagle topped by the crown.

The final test, consisting of a raid lasting an hour and a half, took place on 7 December with the Malpensa-Mirafiori route. Baracca, already considered by his superiors to be one of the most promising and capable students, received the commendation of Giulio Douhet, deputy commander of the Aviators Battalion and future theoretician of air warfare. To celebrate his patent, Baracca returned to Paris for a few days, accompanied by two colleagues and instructor Ugo de Rossi of the Black Lion.

In March 1913, Francesco was transferred to Turin, at the Mirafiori airfield, with the task of taking chronometric measurements of flights during three competitions, called by the Ministry of War, to evaluate aircraft, engines and aviation equipment. Back in Lombardy, in August 1913 he was assigned to the 6th Squadron, under the orders of Captain Marenghi on the Taliedo field. At the end of the month, Baracca took his father Enrico flying, who came from Lugo with other friends. Francesco described that moment as ‘the greatest satisfaction I have experienced during my flights‘. Between the 8th and 18th of September, he took part, with the 5th Squadron, in the Great Cavalry Manoeuvres where some squadrons were deployed in support of ground troops, for a scouting expedition.

On 27 September, Baracca succeeded in his wish to reach Lugo. He flew over his home town and landed near Pratolungo di Fusignano, celebrated by his fellow citizens.

The last few months of the year were not an easy period for Francesco, who was constantly moved between Busto Arsizio and Taliedo, engaged in supervising activities in Varese at the Macchi factories and, above all, entrusted with replacing Lieutenant Calori at Malpensa to instruct the students. This discontent is well expressed in several letters written to his mother Paolina in which Baracca stated bluntly: ‘It is a position of trust, but one that I gladly do without, and I have already lodged my complaint. […] I am very comfortable in my quarters and I would like nothing more than to be left in peace for a while and to finish being a… travelling salesman‘. This difficult phase, in which he had doubts about giving up aviation, faded at the beginning of 1914, perhaps due to a long leave. He returned to Taliedo at the end of February and three months later was put in charge of instructing the observer officers.

When the First World War broke out, in Italy there was a climate of uncertainty and precarious neutrality, which characterised also the following months. In addition, Francesco had to face a difficult professional choice: he had been offered the opportunity to become General Masi’s orderly officer, an option sustained by his mother Paolina. Baracca chose to postpone the decision ‘when this historical moment will pass‘ and added ‘now that aviation has proved to be so useful and as many as pilots are being prepared in a short time, I cannot leave it, especially as I am considered one of the best and most experienced of them‘.

In December, the 6th Squadron, framed in Group II, was transferred to Pordenone, in anticipation of Italy’s entry into the war against the Austro-Hungarian Empire. After months of test flights and reconnaissance of the territory, at the outbreak of hostilities on 24 May 1915, Francesco and some of his comrades were already in Paris, waiting to train on the new Nieuport 10 biplanes destined to equip his squadron.

Il primo soggiorno in terra francese fu, per Baracca, uno dei periodi più felici e spensierati della propria vita . Arrivato a Reims alla fine dell’aprile 1912 , con gli amici e colleghi Umberto Venanzi, Arturo Oddo e Cesare Buzzi Gradenigo; Francesco prese alloggio in una stanza del Grand Hotel, di fronte alla facciata dell’imponente cattedrale gotica.

Oltre a frequentare la scuola di volo presso il vicino campo di volo di Bétheny, il gruppo di ufficiali italiani potè usufruire dell’automobile messa a loro disposizione dal proprietario della scuola , Renè Hanriot, e soprattutto di “pranzi e champagne a fiumi e si capisce perché da noi dipende tutto l’avvenire del suo apparecchio in Italia ”. Pur non essendo un grande centro, Reims offriva numerosi passatempi quali escursioni a cavallo e serate trascorse al Kursaal, un cafè concerto, con molti ufficiali francesi. L’atmosfera che si respirava a Reims, dove continuamente si vedevano “passare motociclette e automobili per terra e velivoli per aria ”, venne molto apprezzata da Francesco, il quale provò un senso di sollievo poiché in Francia, volare era “la cosa più naturale di questo mondo ”, a differenza dell’Italia, dove gli aviatori erano considerati “come dei pazzi, o almeno dei temerari ”. Baracca e colleghi fecero visita anche al console italiano Mazzucchi, proprietario di uno stabilimento dedito alla produzione dello champagne.

Ovviamente non mancò di fare una gita a Parigi, visitando le maggiori attrazioni della capitale come l’Opera, la Tour Eiffel, Les Invalides, il Louvre, Les Tulleries, il Trocadero, il Bois de Boulogne e le corse all’ippodromo di Longchamp, occasione in cui rimase colpito dall’eleganza del pubblico cosmopolita e dove “si sentivano parlare tutte le lingue del mondo”. La sfavillante vita notturna abbagliò la comitiva di ufficiali italiani, che trascorse serate alle Folies Bergère, al Marigny, da Maxim’s, al Rat Mort, da Monico.

Ovviamente non mancò di fare una gita a Parigi, visitando le maggiori attrazioni della capitale come l’Opera, la Tour Eiffel, Les Invalides, il Louvre, Les Tulleries, il Trocadero, il Bois de Boulogne e le corse all’ippodromo di Longchamp, occasione in cui rimase colpito dall’eleganza del pubblico cosmopolita e dove “si sentivano parlare tutte le lingue del mondo”. La sfavillante vita notturna abbagliò la comitiva di ufficiali italiani, che trascorse serate alle Folies Bergère, al Marigny, da Maxim’s, al Rat Mort, da Monico.

L’ambiente parigino piacque così tanto a Francesco che a distanza di poche settimane, vi tornò una seconda volta. In una lettera alla madre Paolina, Baracca notò ironicamente che i restaurants di Montmartre erano “un po’ diversi dalle chiese di S. Francesco e di S. Maria di Lugo”.

Ottenuto il brevetto da pilota aviatore , lasciò a malincuore Reims, osservando con una certa dose di malinconia che “non torneranno per me mai più giorni belli come questi ” ed il 14 luglio , mentre la folla parigina festeggiava per le strade la presa della Bastiglia, Francesco ripartì da Parigi alla volta dell’Italia .

Il soggiorno a Reims a cavallo fra la primavera e l’estate, non fu l’unico in terra francese, durante il 1912: per festeggiare il conseguimento del brevetto da pilota militare, Baracca si recò nuovamente a Parigi in dicembre , dove visitò le officine Nieuport, un’esposizione di automobili ai Campi Elisi, trovando la Ville Lumière “sempre meravigliosa ”.

L’aviatore lughese si recò per l’ultima volta in Francia nel maggio del 1915 per l’addestramento sul nuovo biplano Nieuport 10 presso il campo di volo del Bourget, base della difesa aerea di Parigi .

Dopo nove mesi di guerra, la capitale francese era profondamente cambiata : i locali ed i caffè effettuavano la chiusura alle 22:30, così come i teatri, abiti in nero avevano sostituito le vivaci mise indossate dalle donne parigine e soprattutto la città era colma di ufficiali provenienti da “ogni parte del mondo” in attesa di ritornare al fronte e di soldati convalescenti. In una lettera ai genitori, Francesco descrisse l’austera atmosfera : “Parigi è ora piena di bandiere italiane e tutta la città è imbandierata coi colori delle nazioni alleate. Vi è però assai poco movimento ed un aspetto di serietà che impressiona per chi conosceva prima la città. La sera i boulevards sono quasi all’oscuro […] per l’aria fasci luminosi dei riflettori ed aeroplani che volano a grande altezza con i fari accesi sul carrello d’atterraggio ”.

Dopo aver terminato i voli al Bourget e aver scambiato reciproci auguri con i colleghi francesi, Francesco rientrò in Italia alla fine di luglio.

In France

The first stay on French soil was, for Baracca, one of the happiest and most carefree periods of his life. He arrived in Reims at the end of April 1912, with his friends and colleagues Umberto Venanzi, Arturo Oddo and Cesare Buzzi Gradenigo; Francesco stayed in a room at the Grand Hotel, at the front of the majestic Gothic cathedral.

The group of Italian officers attended the flying school at the nearby Bétheny airfield. In addition, they were able to take advantage of the car placed at their disposal by the school’s owner, Renè Hanriot. Although not a large centre, Reims offered many pastimes such as horse riding and places like the Kursaal, a concert café, where Francesco and his friends spent time with the French officers. The atmosphere in Reims was much appreciated by Francesco: he could constantly see “motorbikes and cars on the ground and aircraft in the air” and flying was considered by the French as “the most natural thing in this world” unlike in Italy, where aviators were considered “madmen, or at least adventurous”. Baracca and his colleagues also visited the Italian consul Mazzucchi, owner of a champagne factory.

Obviously, he did not miss a trip to Paris, visiting the capital’s major attractions such as the Opera, the Eiffel Tower, Les Invalides, the Louvre, Les Tulleries, the Trocadero, the Bois de Boulogne and the races at the Longchamp racecourse, where he was struck by the elegance of the cosmopolitan crowd and where “one could hear all the languages of the world”. The glittering nightlife dazzled the group of Italian officers, who spent evenings at the Folies Bergère, the Marigny, Maxim’s, Rat Mort, and Monico.

Francesco liked the Parisian environment so much that a few weeks later, he returned a second time. In a letter to his mother Paolina, Baracca ironically noted that the restaurants in Montmartre were “a little different from the churches of St. Francesco and St. Maria of Lugo”.

Once obtained his aviator’s licence, he sadly left Reims, saying that “beautiful days like these will never come back” and on the 14th of July, while the Parisian crowds was celebrating the taking of the Bastille in the streets, Francis left Paris for Italy.

To celebrate his military pilot’s licence, in December 1912 Baracca returned again to Paris, where he visited the Nieuport workshops, a car show on the Champs Elysees, and the Ville Lumière “always wonderful”.

He travelled to France for the last time in May 1915, for a training session on the new Nieuport 10 biplane at the Bourget airfield, an air defence base in Paris.

After nine months of war, the French capital changed profoundly: bars and cafés were closing early at night, as did the theatres, black dresses replaced the lively outfits worn by Parisian women, and above all, the city was filled with convalescent soldiers and officers from “every part of the world” waiting to return to the front. In a letter to his parents, Francesco well-described the atmosphere: “Paris is now full of Italian flags and the whole city shows the colours of the allied nations. There is, however, a serious and solemn atmosphere that impresses those who knew the city before. In the evening, the boulevards are almost dark […] in the air bright beams of searchlights and aeroplanes flying at great height with their headlights on the landing gear”.

After finishing his flights at Bourget and exchanging good wishes with his French colleagues, Francesco returned to Italy at the end of July.